Čeněk Růžička: Relatives of the Romani victims of Nazism and survivors disagree with anti-refugee sentiment

Čeněk Růžička, chair of the Committee for the Redress of the Romani Holocaust in the Czech Republic (VPORH), has criticized the absence of any systematic research into the causes and consequences of what happened to Romani and Sinti people during Nazism and the sharing of such information with the public. "For example: How did the arrest of the Romani families by the individual stations of the gendarmerie take place during the Protectorate era? What exactly was confiscated from each family, never to be returned? How did the collaboration of the Czech Protectorate’s Interior Ministry with the Nazis work when it came to the persecution of the Roma?" he asked during last week’s commemorative ceremony, during which he also clearly spoke out against xenophobic populists.

"We Roma today are also concerned about the refugee crisis. We fear its possible impacts and risks in terms of security and social relations. Be that as it may, we also fundamentally disagree with the acrimonious mood of those in this society who are tendentiously inciting political fanatics and populists. After 1989, a time arrived when Romani people were becoming the victims of racial murders, and when Romani people emigrated to more tolerant environments in Canada, England, Germany, the Netherlands and other countries because they feared for the lives of their family members. We were glad that those countries welcomed them with open hearts. We know what it feels like to be migrants and refugees," he said.

News server Romea.cz publishes his speech in full translation below.

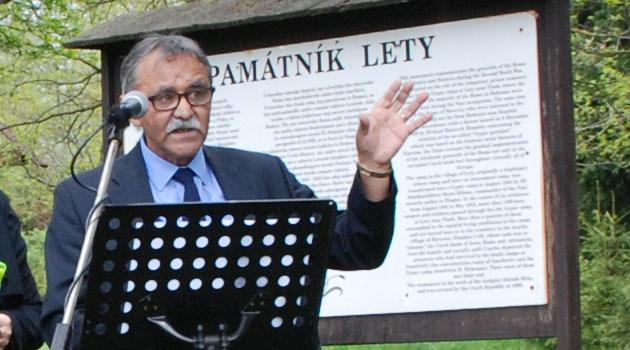

Speech by Čeněk Růžička during the commemorative ceremony at Lety by Písek

13 May 2016

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I would like to read you the statement that I had the honor of presenting in the Senate on the occasion of International Holocaust Remembrance Day in January of this year because I believe it is still applicable today.

The Nazis and their minions destroyed the entire families of origin of both of my parents. My mother never recovered from the horrors she suffered.

During the Communist regime, she was afraid every time she traveled to Lety. She was a direct witness here to the degree to which the places where she had been imprisoned and the graves of her loved ones have been slighted, to an extent that is unlike anything else in Europe.

After 1989, she would turn off the reports of hate marches against Romani people when she saw them on television.

She was unable to comprehend the benevolence shown here toward displays of the same type of hatred she experienced during Nazism. She did not support my activities here after 1989.

She was afraid of the Nazis, she was afraid of the Communists, and she did not stop being afraid, not even after 1989.

Four years ago, during this very commemoration, I raised the question of the lack of systematic investigation into the causes and effects of what happened to the Roma and Sinti during Nazism, the lack of any systematic publicizing of such information, and I expressed the wish that the situation might change for the better in that respect.

The relationships between the majority society and Romani people here are now burdened by an intensity of harmful prejudice to a degree that I have never experienced before. We Roma reach out, we make our arguments, we literally beg, and we still encounter ignorance and incomprehension.

The institutions drawing on the work of the honorable Professor Citbor Nečas publish some historical information here and there, but they constantly repeat the same information – or rather, over the course of time they have just reworded the same information, even though there is a wealth of topics that are worthy of further study.

For example: How did the arrest of the Romani families by the individual stations of the gendarmerie take place during the Protectorate era? What exactly was confiscated from each family, never to be returned?

How did the collaboration of the Czech Protectorate’s Interior Ministry with the Nazis work when it came to the persecution of the Roma?

Under what circumstances were Romani people executed in the Sudetenland after the occupation?

What happened to the 2 500 Roma and Sinti who were unable to respond the situation that arose and who remained in the Sudetenland after it was annexed by Germany?

Those Roma and Sinti never learned from the Sudeten Germans of the imminent danger of their deportation to the concentration camps. With the exception of a couple of individuals, they didn’t know how to read or write.

How did their arrest and deportation to the concentration camps take place in the Sudetenland?

To what degree did the behavior of the Sudeten Germans influence their suffering? Who among them survived those events?

Romani victims from the Sudetenland unfortunately do not show up in the available statistical data.

The surviving relatives of the victims would also like to clarify in more detail the role played by those Romani people who were members of the resistance groups, and it is also necessary to review the brave stories of Czechs who considered Roma to be human beings, and who aided them in hiding during such a complicated situation.

Moreover, we can learn lessons not just from the fates of Romani people during the Second World War, but from the entire history of the existence of the Romani nation.

Ladies and Gentlemen, we Roma today are also concerned about the refugee crisis. We fear its possible impacts and risks in terms of security and social relations.

Be that as it may, we also fundamentally disagree with the acrimonious mood of those in this society who are tendentiously inciting political fanatics and populists. After 1989, a time arrived when Romani people were becoming the victims of racial murders, and when Romani people emigrated to more tolerant environments in Canada, England, Germany, the Netherlands and other countries because they feared for the lives of their family members. We were glad that those countries welcomed them with open hearts. We know what it feels like to be migrants and refugees.

We Roma also have our own experiences with societal rejection from the time of the 1930s.

Regional politicians in those days also hearkened to the voice of the people, who forced democratic legislators to adopt the very law that suppressed my parents’ right to freedom of movement in a fundamental way and introduced discriminatory practices against Romani people.

That law became the cause of the deterioration in what until then had been more or less acceptable relations between the majority and Romani people. It was the legislators who opened the floodgates.

The impacts of that law, which placed Czech Roma and Sinti in the role of second-class citizens, escalated over time into the behavior of the Czech guards toward the imprisoned Romani families inside the concentration camps at Lety here in Bohemia and at Hodonín in Moravia.

I am recalling these facts here out of concern that our society might jump at a similar opportunity to disseminate panic today and might force our legislators to respond rashly. As I have already mentioned, this has happened to us before.

The elections are just around the corner here, and it is apparent that the migration and refugee crisis will tendentiously become a pivotal theme for the candidates. Some of them, especially the fanatics and populists, will be buoyed by this wave of expanding fear and panic, and as we know, fear is a very bad adviser.

Any society can be motivated to commit inexplicable behavior. Naturally, the risk of that now is high, and it would absolutely, certainly be an unforgivable error to underestimate the risk. However, we are Europeans, and as Europeans, we recognize certain humanitarian and moral values. Let’s not let them be trampled on.

Esteemed listeners, I hope we deal with the migration and refugee crisis today in a way that we will not be ashamed of in the future – not as Roma, not as Czechs, and also not as Europeans.

Ladies and gentlemen, there is nothing left for me to do but to thank you, on behalf of the survivors and the relatives of the victims, for your presence here, and naturally we thank you for the beautiful offerings of flowers. Once again, you have aided us in creating a dignified, friendly atmosphere here.

Friends, we will see each other here next year.