Testimonies of survivors of the Nazi-era concentration camp for Roma at Lety in Czech Republic still not discussed

On 15 March 1939, Nazi German leader Adolf Hitler proclaimed the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in those regions of occupied Czechoslovakia. His representatives proceeded to violate the provisions of the Czechoslovak Constitution concerning human rights for the duration of the Protectorate and, in addition to imposing binding, discriminatory regulations targeting Jews, the Protectorate Government, led by Rudolf Beran under the direction of Nazi Germany, also targeted persons living on the fringes of society.

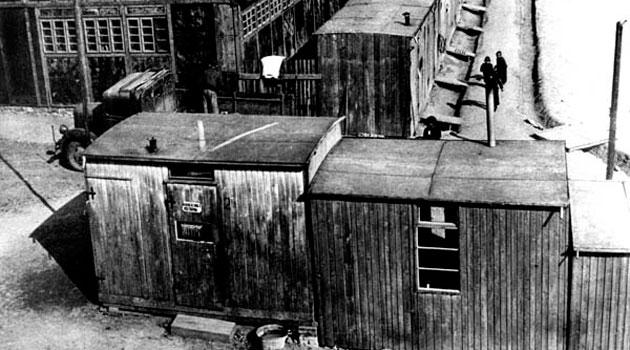

For those purposes a camp was created in the year 1940 in the town of Lety u Písku that was first defined as a labor camp, and later defined as an internment camp. As of 2 August 1942, the term “gypsy” was added to the name of the camp, and its focus was on that particular ethnic group of people, just as the Nazis were focusing on Jewish people, with the aim of physically destroying them, and from our perspective today, Lety is considered a concentration camp even though it did not fulfill the criteria for the definition of a concentration camp that Nazi Germany was using at that time.

Romani people were rounded up in the camp at Lety u Písku – or concentrated, as it were – so they could later be transported to Auschwitz, where death awaited them. A total of 420 prisoners were transported to Auschwitz from the Lety camp, and almost the same number of victims perished on Czech soil in the camp at Lety.

A large number of victims, however, died especially because of the catastrophic conditions that prevailed at Lety, which the camp leadership not only ignored, but even created. The undisputed culprit in this crime, who was identified as such by several witnesses among the guards who were later interrogated about Lety, was the camp commander, Josef Janovský.

Two outhouses for 1 000 hypothermic prisoners

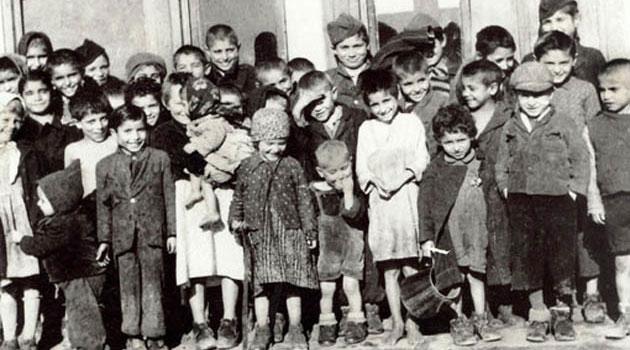

Janovský absolutely underestimated the capacity of the camp, which had been designed for roughly 400 persons, and accepted a total of 1 145, which from the political point of view was connected with the proclamation of the decree on combating the so-called “gypsy nuisance”. Entire families were transported to the camp in wagons, accompanied by the gendarmerie.

Such an enormous onrush of prisoners made itself felt on the overall running of the camp almost immediately, as it was not prepared at all for the situation that arose. In the sleeping quarters, which were wooden barracks, those who were interned were crowded without even the most basic toilet facilities.

As guard František Kánský testified, there were just two common outhouses for the entire camp. The physician František Kopecký visited the camp and described how the prisoners had to wake up a gendarme to access the outhouses to relieve themselves at night, and since the gendarme would beat them up when they did so, they were forced to relieve themselves in their sleeping quarters.

“The consequence of these circumstances, soon after the gypsies arrived, was a mass epidemic of diarrhea, but the gypsies were not separated from each other and slept together,” Kopecký reported. In the winter months, the prisoners were given hardly any coal to burn in their decrepit wooden barracks, and most of those interned at Lety suffered from severe hypothermia as a result.

“(…) in the barracks it was so cold that the ink in the inkwell was frozen by morning. The prisoners were supposed to be given coal for their barracks as per a directive issued by the district authority. … Janovský, however, kept that coal and doled out – or rather, caused to be doled out by his subordinates – a very fractional amount of it to the prisoners. Sometimes he would not give them any. The prisoners were terribly cold and therefore walked into the nearby forest for firewood and kindling,” described František Malík, who was the camp’s economic manager.

Besides the substandard hygiene, enormous malnutrition predominated among those interned at Lety, caused by the fact that Janovský also kept back the food intended for the prisoners. “I also heard that the groceries intended for the prisoners were sent away from the camp, the prisoners told me that, and the accountant Novotný mentioned it also, but he told me it could never be provem, as the books are all in order,” František Kopecký said.

The starved prisoners received moldy food, according to eyewitness testimonies. The physician Jan Neuwirth visited the Lety camp and described what he saw there as follows: “[upon my arrival] I ascertained the following: Absolute malnutrition, filth, and an infestation of vermin, and therefore I immediately contacted Josef Janovský and demanded that he increase the amount of nutrition provided, as I personally am convinced the gypsies are receiving moldy potatoes to eat and cabbage that is just as moldy. […] Janovský excused his behavior by claiming he did not have enough supplies for those interned, but I myself saw, in his office, crates of artifical fat and preserved bacon, and I also heard from other gendarmes […] that Janovský was sending the groceries that were supposed to be given to the gypsies to the authorities in Prague.”

An image from Dante’s Inferno

The most serious human failing committed by the camp leadership and the subsequent mass death of those interned there, however, is considered to be the fact that they ignored the continually-deteriorating state of health of the prisoners, as a result of which epidemics of both typhoid and typhus spread throughout the camp. “With respect to the aspect of health, nothing was done. The necessary drugs and staff were not available. Whenever I ascertained somebody had an illness and required transportation to a hospital, Janovský cancelled my recommendation without explanation,” physician František Kopecký, who worked at Lety from 1941 – 1942, reported.

In January 1943 Jan Neuwirth took office as the attending physician at the camp and had to face the high rates of illness and mortality that were growing to catastrophic dimensions. In his daily report from 26 January 1943 he wrote the following, among other things: “many prisoners are in such a rueful state that it is necessary to consider them hopeless cases. Their demise can no longer be prevented.”

In order to investigate whether what was actually happening was a typhus epidemic, a leading Czechoslovak microbiologist, František Patočka, was summoned to the camp and provided this horrifying testimony about the child victims he saw during his visit to Lety:

“The gypsy children, except for the newborns and the youth who were capable of work, were separated away from their parents into two big barracks, where, on bunks covered with moldy straw, most of them were left to their fate. Approximately three times a day a gypsy woman brought them a pot of some sort of food, which she distributed along the edge of the bunkbeds. The “meals” for the gypsy offspring were rather more like a very miserable feeding time in a zoo. Most of the children were wearing just a shirt that was falling apart, while some were absolutely naked. The only bedcover for the herd of children was a large piece of canvas sail which was not enough to cover them all. They pulled it back and forth among themselves, not just with their hands, but also with their teeth. In order to ascertain the actual state of the hygiene beneath the canvas, I removed it entirely. The very first thing that I became aware of, to my horror, were the little corpses of other children lying there. The second, maybe even more horrible thing was the look of the children who were in agony, some of them with fever. I can recall absolutely clearly, to this day, that the image I beheld exceeded even the most tremendous description of Hell in terms of the horrors I saw there. I was unable to explain the dying children, and especially their gangrene. Another visit to the camp showed me that even among the adult population a febrile illness was underway, one that for me at the time was unprecedented in its nature, ending either in death, or in such a difficult convalescence that even young patients were almost unable to move as a result.”

Responsibility of the Czech administration

A total of 241 children, three adolescent males, four adolescent girls, 48 women and 30 men died at the camp in Lety u Písku. Most of the prisoners who managed to survive ultimately ended up in the transports to Auschwitz, where most of them awaited death.

As the historian Petr Klinovský writes in the epilogue to his study on the guards at Lety, even though the transports to Auschwitz are not to be blamed on the Protectorate authorities, the camp at Lety u Písku was under the de facto influence of the authorities and bureaucrats of the Bohemian part of the Protectorate. Each victim is, therefore, not just a victim of Nazi madness, but also of the Protectorate administration.

Sources used

- Červenka, Juraj.: Škvrnitý týfus [Spotted Typhus]

- Klinovský, Petr.: Lety u Písku. Neznámý příběh dozorců [Lety by Písek: The unknown story of the guards]

- Nečas, Ctibor.: Holocaust českých Romů. Svědectví těch, kteří přežili Lety [The Holocaust of the Czech Roma. Testimonies of those who survived Lety]

- Státní oblastní archiv Praha [Regional State Archive, Prague]

- Státní oblastní archiv Třeboň [Regional State Archive,Třeboň]

This article was first published in Czech as part of the Czech Government’s HATE FREE project.