Karski reported the Holocaust as it was underway, no one believed him at the time

Disguised, he accessed the places where the Nazis were committing their greatest atrocities. He was the first to provide the American and British authorities with complete testimony regarding conditions in the Warsaw ghetto and the death camps.

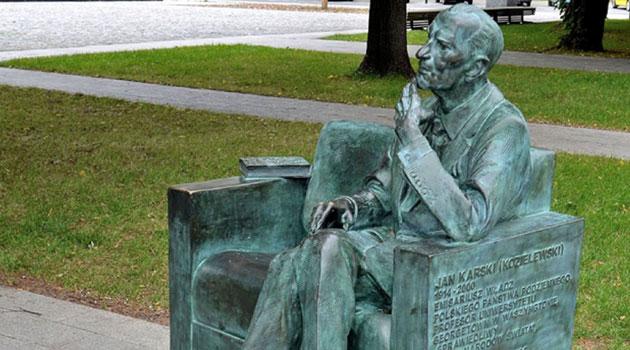

Jan Karski, the legendary courier between the Polish resistance and the Polish government in exile in London, met with the world’s leading politicians in that role. His efforts, however, received no response at the time.

The world was unwilling to believe his testimony and took no action to stop the Holocaust in which six million lives were lost. Today marks 100 years since his birth into a Catholic family.

The life of Jan Karski would be enough for several novels. As a soldier in the Polish Army he was captured by both the Germans and the Soviets, and he was arrested during his mission as courier more than once.

Concerned he might reveal secrets under torture, he once unsuccessfully attempted suicide. During his efforts to stop the Holocaust he also met with the very highest world politicians and other leading figures.

After the war Karski settled in the United States. What he had done during the war was not known for a long time afterward.

Karski was born Jan Kozeliewski on 24 June 1914 into a Catholic family in Łódź. His father was the owner of a small factory that produced leather goods.

Some sources list his birthday as 24 April, but Karski himself, in several documents written in his own hand, says it was in June. He was a pious Catholic and grew up in a multicultural environment given that a large proportion of the inhabitants of Łódź were Jewish.

His strongly religious mother raised him to be tolerant of minorities and had an enormous influence on his youth. After graduation, Karski studied diplomacy and law at the University in Lviv and worked for the Polish diplomatic services starting in 1935, with postings to Britain, Germany, Romania and Switzerland.

At the start of 1939 he was hired full-time at the Polish Foreign Ministry, but in August he received his mobilization order and began serving with an artillery regiment. When Poland was partitioned between Germany and the Soviet Union, he found himself captured by the Soviets but managed to conceal his actual value as an officer and to be exchanged with the Germans.

In this way Karski avoided the fate of the thousands of Polish officers who were massacred by Stalin’s NKVD police at Katyn. He succeeded in fleeing German captivity, made it to Warsaw, and joined the resistance movement.

In January 1940 he was sent to Paris to establish contact with the government in exile, headed by General Władysław Sikorski. He traveled for three weeks across Slovenia, Hungary, Yugoslavia and Italy to reach the French capital.

In May of that year he was sent once again to Paris. However, on the way his identity was revealed and he was arrested by the Gestapo in the Tatra Mountains of Slovakia, who cruelly tortured him.

Karski lost almost all his teeth but never betrayed either his colleagues or his mission. The Germans transferred him as an important prisoner to a hospital in the small occupied Polish town of Nowy Soncz.

With the aid of several people who were later executed for helping him, he succeeded in fleeing. After a brief convalescence, he returned to service in the Department of Information and Propaganda of the Polish Home Army Command.

In 1942 Karski set out on what was probably his most important mission ever. The goal was London, where the Polish government in exile was headquartered after the fall of France.

Karski was meant to inform the prime minister of the government in exile, Sikorski, as well as other politicians in the UK about the Nazi atrocities in occupied Poland. Jewish people had arranged for him to make two secret visits to the Warsaw Ghetto.

"It had nothing in common with human beings, I had never experienced anything like it before," Karski says in Lanzmann’s documentary film "Shoah" of 1977. He was talking about the streets lined with piles of garbage topped by naked corpses.

He experienced the filth, the nervous rush, and the stench of it all. "Remember what you have seen here, tell people outside about it. Don’t forget!" his Jewish guides exhorted him.

Disguised as a Ukrainian officer, he also accessed a transit camp in the town of Izbica Lubelska. His painful journey to London led across France, the Pyrenees, Spain and Gibraltar to England, where he succeeded in delivering microfilms of an extensive report about the Polish resistance movement and the Holocaust of the Jews in occupied Poland.

The Polish Foreign Affairs Minister, Edward Raczynski, could have provided the world at that time with one of the first and most precise testimonies about the ongoing Holocaust. However, Karski did not succeed in his mission, despite his urgent requests for aid to the Jews from the British Government.

Karski did not give up and flew to the United States, where in 1943 he even met with US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He was not successful there either, and the world took no action to stop the Holocaust.

The interview he had with US Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, who was of Jewish origin, was symptomatic of the times and has been widely quoted ever since. Frankfurter calmly listened to Karski and then said to him: "Young man, I don’t believe you. I’m not saying you are lying, but I don’t believe you."

After the war, Karski departed for the USA. He graduated from Georgetown University, where he then lectured.

In the US he married the Jewish choreographer and dancer Pola Nirenska, whose entire family, almost, had perished in the Nazi death camps. His efforts to stop the Holocaust was forgotten until the end of the 1970s, when they were revealed by Claude Lanzmann’s famous film "Shoah"; his books, which were all but unknown until then, also helped.

Karski passed away on 13 July 2000 at the age of 86. He received many awards for his efforts to stop the Holocaust, including the title of Righteous among the Nations.