Czechoslovak Legionnaires on the Italian front - Romani fighters and their sad fates

As part of celebrating 100 years since the creation of the Czechoslovak Republic, the famous Czechoslovak Legionnaires who fought on three fronts (France, Italy and Russia) are being commemorated for making it clear to the world which side of the First World War the inhabitants of Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia and Slovakia stood. Under the command of their main leaders, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk and Rastislav Štefánik, they made visible the desire of Czechoslovaks for their own state and for separation from Austria-Hungary.

The credit due to these fighters for the achievement of independence, as well as disseminating the idea of the shared republic, is indisputable. It is interesting and, to this day, very little known that their ranks included not just Czechs, Germans, Jews, and Slovaks, but also Romani people.

It was not easy to join the Czechoslovak Legion – the soldiers were warned by pro-Austrian officers not to do so, they threatened deserters with execution and with official retribution against their families. Especially difficult considerations were faced by the Legionnaires who had been captured by the Italians, where the Czechoslovak preparation committee was unable to achieve recognition of them as divisions of the Legion because the preparatory phase lasted many seemingly endless months.

During the first battles fought by the Legionnaires against the Austrian Army, the Czechoslovak prisoners (deserters) who were apprehended actually were hanged by the Austrians in order to set an example. Despite that fact, 20 000 Czechoslovaks gradually joined the Legion.

This article will recall three of them: Josef Holomek, born 1876 in Hluk, registered in Uherský Ostroh; Adolf Ištvan, born 1880 in Jihlava, registered in Bohusoudov; and Štěpán Holomek, a member of the younger generation born in 1898 in Kunovice, where he was also registered – for all three it is possible, according to local records, to document the fact that they came from Romani families. For all three it is also apparent that they volunteered immediately during the first weeks of the Legionnaires’ existence.

It is not likely these fellow Legionnaires from the Romani community ever met each other in the Legion. While all three took their oaths in the same (and the biggest) prisoner of war camp in Padula, Italy, each one took his oath on a different day and was assigned to a different unit.

Štěpán Holomek was assigned to the 31st regiment, Josef Holomek to the 32nd, and Adolf Ištvan was first assigned to the 32nd but shortly thereafter was reassigned to the 33rd. Their personal files do not note their having been given any special promotions or recognition.

Mentions of that kind are rather found for the more numerous group of Romani Legionnaires in the division that fought in Russia. Nevertheless, this article will focus just on these three Legionnaires who served in Italy.

As Legionnaires serving in Italy, they all have something in common besides being Romani. When I read their personal files, kept in the Military History Archive (the collection of the Office of the Legions – KLEG), I was especially captivated by the correspondence concerning the payment of their wartime service pensions during their time in Italy.

All three negotiated two different wartime service pensions with the Italian Government, one for 500 Italian lira and another for 1 000 Italian lira, in case of their deaths, with the additional clause that should the soldier survive the war, the policy would pay out within a certain time frame. Each indicated the person to whom the pension should be paid in case of their deaths.

All three soldiers managed to survive battle and to return – certainly with a great amount of honor and glory – to the country of Czechoslovakia, which was officially established by then. All three, however, came home wounded – Ištvan had been shot twice, Štěpán Holomek was treating frostbitten feet and apparently had neurological difficulties, and the oldest of them, the blacksmith Josef Holomek, was gravely ill and died in 1936 in his home in Ostrožské Předměstí of liver cancer – or as the priest there recorded, “in a gypsy hut”.

The fact that Josef Holomek (or rather, his heirs) actually received a payout from his Italian wartime service pension given his early death was due to his fellow Legionnaires from Uherský Ostroh. Just after his death they did their best to ensure the pension was transferred to the common bank account of Josef Holomek’s widow and their children (established in 1938 in the name of Běta Holomková, apparently his daughter, while the signature on the remit is that of Anna Holomková. his widow; the amount of the disbursements was CSK 752.55).

What’s more, Josef Holomek received one more honor from his fellow Legionnaires: They organized a funeral attended by 60 Legionnaires at which they gave speeches and later also produced written testimonies honoring their “gypsy brother”.

As for the other two Romani Legionnaires from the Italian front, unfortunately they never saw their pensions disbursed, although both of them did their best to file claims for reasons of illness and the need their families were experiencing. The older Legionnaire, Adolf Ištvan, sent two requests to the ministry (KLEG), one in 1924 and a second in 1936.

At the time Ištvan was living with his family in his home town of Bohusoudov – the biggest Romani diaspora on the border of Bohemia and Moravia. As he stated in one of the applications, “Since I am now infirm and unable to work and I have four children whom I am unable to afford, I am kindly asking whether these pensions could be disbursed to me now, and I also would like to know where I am to go to receive them, as at this moment I find myself in a difficult financial crisis and I need this money urgently. With respect and fraternal greetings, Adolf Ištvan.”

The youngest of the three, Štěpán Holomek, has four letters preserved in his file. The first is from 1929, where he asks for a copy of his pension card, as he had lost the original immediately after being released from service when he was hospitalized and underwent serious operations.

He mentions that loss in his letter: “I myself did not know they had brought me there, they burned my clothes and when I left, I was looking for my pension cards in my small wallet and there is a bit of contention over this now.” His other letters are requests for immediate disbursal of the pensions and are sent between 1930 and 1934.

In them he explains his difficult situation: “This money is needed for my home, I am living in a bad place. [….] I am absolutely dispossessed, partially invalid, during the last maneuvers they operated on my stomach and there was some sort of operation near my heart. I am not receiving any disability pension and now I am building a small house for my family and doing it all on credit. If I didn’t have to complete it, I would not keep building, but we are overcrowded, seven adults in a 2×2 [this is apparently a reference to square meters]. It is unbearable. I am anticipating the birth of a child soon.”

Several months later, he urges that his request be met by making a particular moral appeal: “… given what I have suffered for the future generations and for you, I cannot be left a pauper.” All of these letters received practically identical answers from KLEG at the Ministry of National Defense, first handwritten ones and later pre-printed forms with the name, address, salutation and date added by hand: “Pensions for Italian Legionnaires are disbursed either 1) after the death of the insured legionnaire to the heirs listed on the insurance bond, or 2) in the year 1948 to the insured legionnaire.”

The only thing that might have been a comfort to the person receiving such a letter would have been the familiar form of address, such as: “Dear Brother Ištvan Adolf, Bohusoudov u Budče, we are responding to your letter as follows…”. The use of the familiar, more intimate grammatical form may have recalled for them the revolutionary spirit of their having gone together into the battle for an independent state when, in a revolutionary spirit full of enthusiasm, all these soldiers addressed each other familiarly and called each other “brother”.

At that time differences between the poor and the rich were erased, and the borders between non-Roma and Roma – which earlier, unfortunately, had been a matter of course and would later be erected once more – did not exist. It is a tragic fact that both these applicants, Holomek and Ištvan, never did live to see their anticipated reward, but instead experienced cruel racial persecution, and they did not survive until 1948.

I have not yet managed to ascertain whether they ever received any other recognition for their bravery, as their older “brother” Josef Holomek did. Both became victims of the Nazi genocide along with their families.

Adolf Ištvan was part of the first transport that left Bohusoudov and traveled straight to Auschwitz-Birkenau. On 7 March 1943 the prisoner number Z-969 was tattooed on his left forearm, according to the records of the “Gypsy Family Camp” there.

Both soon met their death in that camp, dying there on 30 June 1943. Štěpán Holomek was registered in the records as arriving one day after Ištvan and being tattooed with the number Z-1241.

After the Second World War ended, none of their surviving descendants sought to have their life insurance disbursed. For the time being it is not known whether any other keepsakes have been preserved about them other than local official records or registers and the military documents about their brave sacrifice when joining the Czechoslovak Legion.

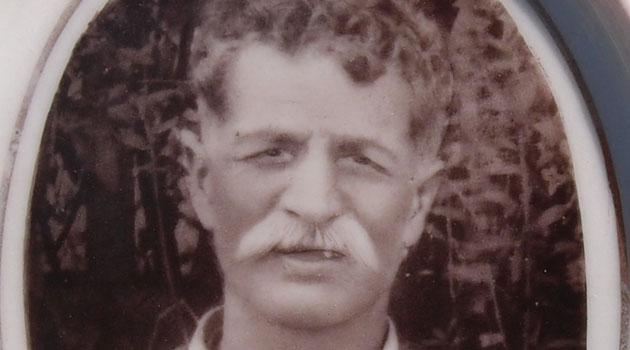

Josef Holomek is the only one of the three whose photograph still exists. What is left of the other two are just their oaths, their Legionnaires’ military identification, and the above-mentioned letters.

Romano vod’i magazine is working on another installment for our series of articles about Czechoslovak Legionnaires from the Romani community. If you have any proposals for us about any other still-unknown Legionnaires whom we could write about, or photographs from those days, please do contact the author of this piece, Lada Viková at lada.vikova@upce.cz – and thank you!

First published in Romano voďi magazine (www.romanovodi.cz). The magazine is produced with the financial support of the Czech Culture Ministry. This thematic issue was also produced thanks to the financial support of Germany’s EVZ Foundation (Remembrance, Responsibility, Future).